Mind the Gaps

The GTA is spending more on new transit than any other city in North America. But it's neglecting one of the most critical elements of any transportation network.

- Reece Martin

- Feb 22, 2023

Map by Bjoern Arthurs

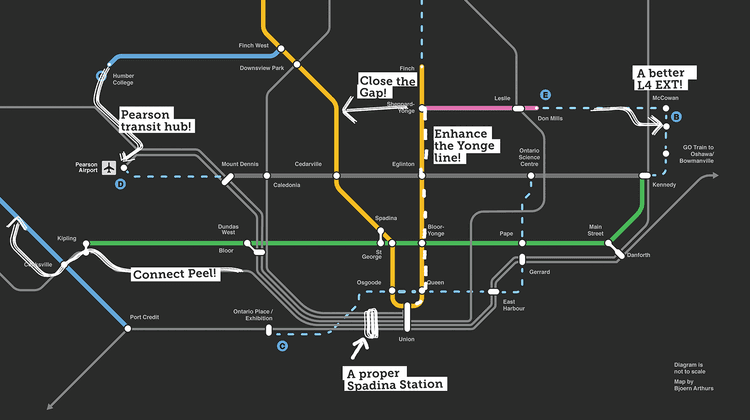

THE TORONTO REGION is spending more on building public transit than any other city in North America—and possibly more than almost any other city in the western world. At present, two major new subway lines are under construction or in the pre-construction phase, two major subway extensions are under construction, two new surface light-rail lines are under construction, numerous existing subway stations are being upgraded and made accessible, the regional rail network is being prepared for electrification, and numerous other billion dollar–plus projects are being moved forward or built. All this in jurisdictions that have historically failed to get things done. Unfortunately, while we are finally getting things done, in the rush to build, it seems not nearly enough attention is being paid to one of the most critical elements of any transportation network: the fact that it is a network. We aren’t maximizing the benefits of the transit we have already built, and we won’t get as much as we could or should out of the new transit we are building, because we don’t take seriously enough the idea that, to serve a community or a region, transit needs to operate as smoothly and efficiently as possible as an integrated system. Continuing to build in this way is wasteful, and it leaves residents, businesses, the economy, and the environment throughout the region suffering unnecessarily. A commitment to network optimization in transit planning would mean that we focus on removing bottlenecks and increasing capacity within the transit systems that currently exist, and it would require new transit projects to integrate as seamlessly as possible with those systems. It would mean prioritizing projects that serve the greatest number of riders or provide the greatest relief to overstrained infrastructure and that do so as cost-effectively as possible. And it would make funding for new transit projects contingent on meeting these standards. Our failure to take this network-first approach to transit means that new projects are often decided by political whim—that is, at the whim of politicians who serve constituents in a very particular location—rather than on more objective criteria that benefit the system as a whole. Instead of prioritizing projects based on which ones would net the greatest number of new riders or provide the most value for money or enhance the network the most, it feels like priorities are set by whatever stakeholder groups can make the most noise and convince the political powers of the day to build (or refrain from building) something in their neighbourhoods.

A GOOD EXAMPLE of the dysfunction that plagues our approach to transit can be found in the major Line 5 Eglinton project, a new light-rail line on Eglinton Avenue. The western portion will operate just like a subway, without street crossings or interactions with cars, while the eastern portion will operate similarly to surface routes such as the 510 Spadina or 512 St. Clair streetcars, with trains running down the middle of the road and needing to stop at intersections and popping underground to enter major stations. The issue is where the transition between these two portions of the route takes place. Science Centre Station, at the intersection of Eglinton and Don Mills, is a major hub, where the heavily used Don Mills and Lawrence East buses as well as the future Ontario Line subway will all terminate. A massive amount of transit-oriented development is already rising from the earth here. Surely, given this concentration of activity, Don Mills is the surface-to-underground transition point on the new Eglinton line? Unfortunately not. The subway-style operation of the Eglinton line will end at the comparatively quiet Laird Station, roughly two kilometres to the west. What’s even more frustrating is how little prevents the more frequent and reliable subway-style service that the western part of the Eglinton line is likely to see from extending all the way east to Don Mills. The main barrier to operating subway-style service above ground is what is known as “grade separation”—which simply means that you keep the light-rail vehicles isolated so that they do not need to stop at intersections the way cars, cyclists, or pedestrians do. (Think about the above-ground portions of the Yonge subway line as an example.) This ensures trains can operate quickly and frequently, often in a semi-autonomous way that depends on advanced transit-specific signals (like high-tech traffic lights but for trains). As luck would have it, the Eglinton line between Laird and Don Mills is almost 100% grade separated, with just a single T-shaped intersection interrupting it at Leslie Street, which begins at Eglinton and runs north. All that would have been required to attain total grade separation for the new transit line along this stretch of Eglinton and allow for that better, more attractive subway-style service? Moving the tracks to the south side of the intersection or building an overpass to span it. But neither of these is being done. If you were to say that this seems like a silly obstacle to running optimal service to what will be one of the city’s most important transit hubs, you’d be right. You might wonder why the plans for the Eglinton line were never revised to fix these issues. To some extent, it’s because the project had already been designed by the City of Toronto when it was taken over by Metrolinx, the regional transit authority; given the tumultuous history of the project, the desire to forge ahead and just get things done prevailed. Of course, avoiding what may have been a few months or a year of redesign work in the early 2010s will likely mean an expensive and time-consuming change sometime in the future. These kinds of network gaps tend to crop up surprisingly often in Toronto’s transit network, and I’d argue it’s because serving new areas often takes priority over building a strong, high-capacity network. Another connection I seriously wonder about is the lack of a rapid transit east–west across the north of the city. There’s simply no direct way to get from northern Scarborough to northern Etobicoke or from North York to York University. Filling in this gap with a Sheppard West or Finch West line would make the existing system much more useful. However, a project like that doesn’t feature at all in the province’s Connecting the GGH transportation plan. A Metrolinx assessment from 2020 rated a Sheppard West project very highly in terms of its ability to optimize the existing transit network and meet the demands created by density along the corridor; unfortunately, it ranked very low in terms of readiness—planning and funding for the line are basically nowhere. I would suggest that priorities are misplaced here: other projects that do less for the overall transit network have received billions in funding.

THIS FAILURE to take network optimization seriously isn’t confined to the TTC. Another project being built in a way that needlessly slows down the system as a whole is the Hurontario LRT in Peel Region. Setting aside the question of whether a slower-moving surface route, which will be subject to interruptions from street traffic, is the most appropriate way to provide transit service to the central corridor of a region of over a million people, the Hurontario LRT won’t even go to all of the places it needs to. While the line will connect major nodes such as Port Credit and Cooksville to important destinations like Mississauga City Centre and the Brampton Gateway terminal, it will not continue all the way into downtown Brampton. This seems like a minor issue until you realize that downtown Brampton is a regional transit hub in the making. Without a connection to Brampton Station on the Kitchener GO line, riders from Toronto hoping to travel along the tech corridor to Kitchener, Waterloo, and Guelph, or residents from that corridor making the reverse trip, will all have to put up with a needless and inconvenient stint on a bus in the middle of their journeys. Fewer riders will use transit to make these regional trips—and will generate more emissions via car use—as a result. So why was the line cut short instead of running all the way into downtown Brampton? The simple answer is that, as is far too common, local politicians claimed they had concerns about the streetcar-like line’s ability to blend into the city’s historic downtown. This was a very questionable stance, given the historic importance of such modes of transit in North American cities. (Far more sacrosanct historic sites, such as the Colosseum in Rome, have trams running adjacent to them.) If decision makers at the province and at Metrolinx had been more committed to getting the most out of this new project, they could have made funding for rapid transit in Brampton contingent on this new route being integrated into the regional network. Instead, we have a line that, while useful, does not play nearly as big of a role as it should.

THE INEFFICIENCY in how we are building out transit—because failing to optimize our networks is a form of inefficiency—is compounded by inefficiency is the projects we allocate funding to in the first place. The Toronto-York Spadina subway extension to York University was among the most expensive subway projects per kilometre ever built in North America, despite mostly running under open spaces and industrial lands, and includes many of the least used subway stations in the city. More transit-oriented European and Asian cities can build entire transit lines for the cost of a few of the stations on that route. The reasons why they can do this so much less expensively are complex but include greater standardization, more efficient procurement models, and a preference for outsourcing expertise and design. To the north of Toronto, in York Region, is a beautiful new bus rapid-transit (BRT) network known as VIVA, with soaring stations built of steel and glass. Yet if you show up at one of these stations, you’ll often wait 20 minutes or more for a bus, even while buses just a bit south in Toronto will run every five for most of the day, despite getting stuck in traffic—exactly the type of thing BRT infrastructure is supposed to help with. If leaders were genuinely committed to the health of the overall transit system and to getting the greatest value for the greatest number of riders in the region, the capital dollars used on York’s large but underused BRT network would have gone first to other pain points, like Bloor-Yonge station in Toronto: the billion dollars that was spent to create the new bus lanes in York Region is about as much as you’d needed to fix Toronto’s main subway interchange, which also happens to be the busiest transportation hub in the country. (Does that mean we’ve wasted all this money on bus infrastructure? Of course not. York Region simply needs to step up to the plate and build a city to match the transit infrastructure it now has. Not parking the buses in the middle of the day and on weekends would be a good start.) Which brings us to the matter of jurisdiction. When travelling in the GTA, transit riders face something that drivers do not: they are crossing borders. While in a car, you seldom notice when crossing a municipal boundary; your trips are seamless. This could not be further from the truth on transit. Travelling from one bordering municipality to another, like going from Toronto to York Region, usually means switching from one bus company’s bus to another, even to continue up the same street. Moreover, passengers usually need to pay again for the privilege of getting this experience! It’s yet another way that we are failing to optimize our transit network. In most major cities, from London to Paris to Tokyo, the integrated transit smart cards (akin to the Presto card) were introduced years ago to help make travelling from one municipality’s system to another’s effortless. Moreover, the relevant cities, transit agencies, and authorities came together to ensure that passengers travelling in a way that alleviated pressure on the overall system paid the best, lowest fares. In London, for example, if you take a longer trip in order to avoid central areas of the city or travel during less busy times, you’re given a discount. Efforts to fix fares in the GTA have been modest; instead of getting everyone into a room and hashing it out, agreements are usually struck between various individual pairs of transit agencies. This further complicates the fare system: some agencies have carve-outs for one another, some allow free transfers, some require tapping on and off, some just tapping on. Last year, the Toronto Region Board of Trade developed a plan to show what it would look like if all the transit agencies in the region were integrated into a single zonal fare system in which virtually no trip would come at a higher fare than it does today. The costs of the integration were modest—about $100 million, less than 10% the cost of one of the many new rail lines we are building. Unfortunately, there appears to still be no momentum from transit agencies or the provincial government to implement such a plan, though promises for further studies have, as usual, been made.

FINALLY, WE COME TO THE ISSUE of regional rail. The GTHA is spending billions to completely transform our North American–style commuter train system into something very much akin to the S-Bahn train systems of Europe. Slow, infrequent diesel trains taking people into work in the morning and out in the evening will be replaced with fast electric sets running every few minutes on most lines late into the evening. It’s a project without any comparable precedent in North America, and it’s been slowly progressing over 10 years as, piece by piece, the entire commuter rail network is modernized and upgraded. While the effects of this haven’t gone completely unnoticed, it feels, as it often does in this region, like we are building our rail network for the city of yesterday rather than the metropolis of tomorrow. Many of Toronto’s most popular and rapidly growing neighbourhoods, from the Junction to the Distillery and Canary districts to Liberty Village to CityPlace, exist in spaces directly adjacent to the regional train lines that are in the midst of being upgraded. But most of these communities are only marginally served by the fast, high-capacity regional trains, if they are at all: when the neighbourhoods were built, they didn’t have stations from any of these lines. We missed out on an opportunity to cost-effectively serve some of the nation’s fastest-growing neighbourhoods—none of which have great subway access—and we have disproportionately concentrated the benefits (and pressures) of the immense capacity offered by these lines to the area around Union Station. This is changing but not enough: some neighbourhoods, including Liberty Village, will get new stations in the course of the commuter rail upgrades, but other locations, like the Distillery, won’t be. While East Harbour, currently an unused industrial site, will get its own new, massive transportation hub—likely owing to smart planning and advocacy by its developers—those living in the forest of towers at CityPlace, just a short distance down the line, probably won’t. Even where we are adding new stations, they are only going to be at a fraction of ideal capacity: residents of the CityPlace neighbourhood will be able to catch a train to Barrie but not to Mississauga, Brampton, Hamilton, Kitchener-Waterloo, or Pearson Airport—all of which could be connected at this site but won’t be. Eventually, we will realize that all these communities need stations, or need better services at the stations they have, and we will be forced to spend far more money down the road to rectify these mistakes and provide them. The Toronto region is doing more than most in North America to fix the situation it’s in, and it’s important to remember that. My frustration doesn’t lie in us failing to achieve anything. Rather, my frustration is that we are so close to something great, and yet we get in our own way before we manage to achieve it.

Reece Martin is a transit advocate and content creator in Toronto who covers public transportation and railways around the world.