Cutting Corners: Angular Planes Are Costing Us Homes

The little-discussed design requirement that is contributing to our housing crisis.

Rendering of a proposed condo development by Diom Development

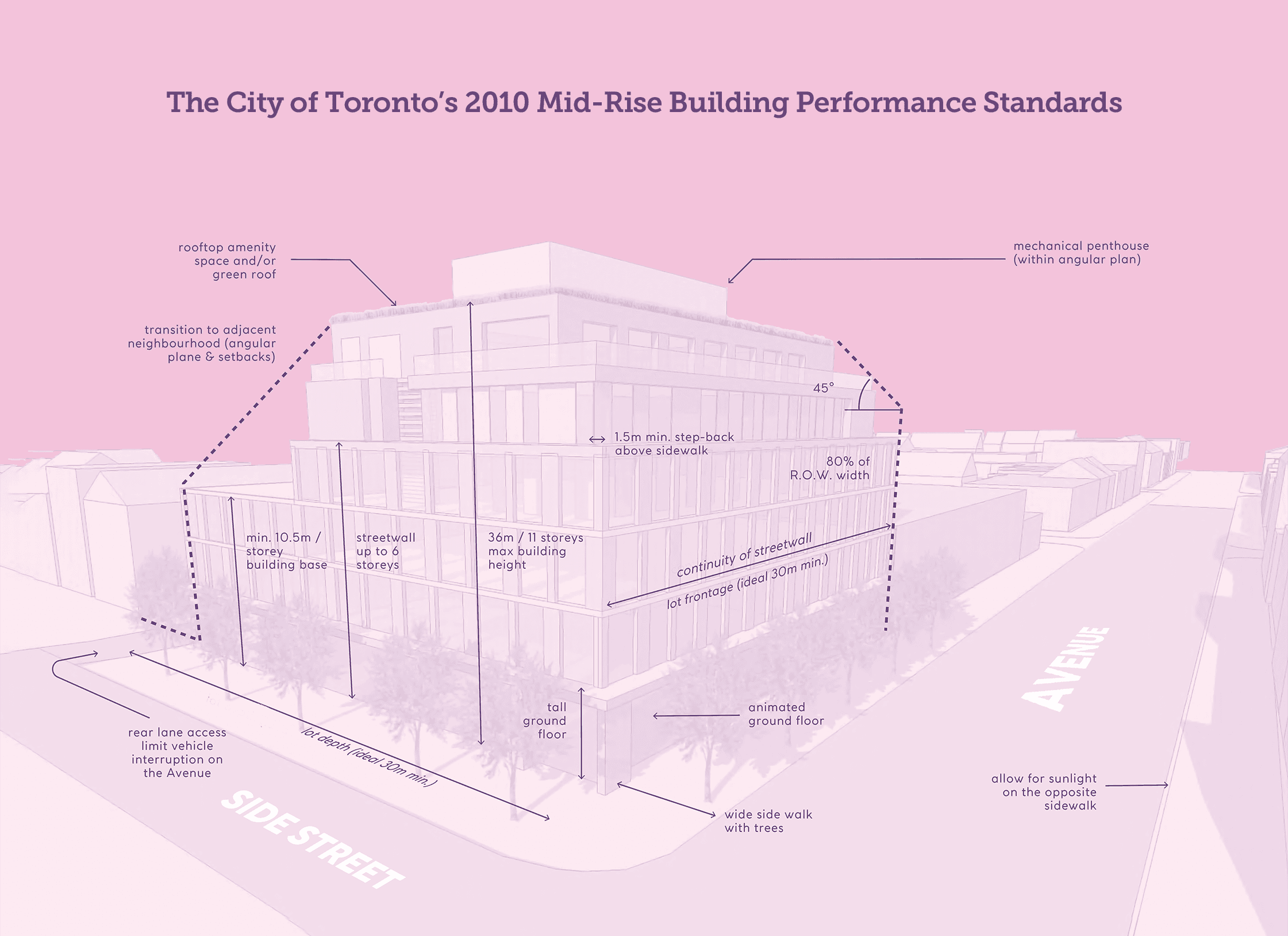

YOU HAVE PROBABLY NOTICED that many mid-rise buildings in Toronto are shaped like wedding cakes or staircases. This is not a coincidence or a reflection of architectural trends: it’s a result of applying a municipal urban-design guideline known as the angular plane provision. The guideline requires buildings of a certain height to have sides that, roughly speaking, slope inward, creating buildings that are wide at their base and narrow toward the top. The intention is to minimize shadowing, allowing a certain amount of sunlight to reach the street and backyards below. More technically, the angular plane is an imaginary line following a 45-degree angle, which cuts away pieces of the front and back of a building; in practice, buildings that conform to this provision are generally tiered—creating that wedding cake or staircase look.

Angular planes apply to both the fronts and backs of buildings, and how they are calculated depends on a range of factors, including right-of-way, lot size, and building type. According to the City, the front angular plane is intended to maintain a desirable streetscape by allowing for a minimum of five hours of sunlight to hit the street below; the rear angular plane aims to provide an appropriate transition to adjacent low-rise homes and parklands. Applying an angular plane to new mid-rise developments supports the growth of a friendlier city, the rationale goes, by minimizing the impact of new construction on existing housing and amenities—it’s a form of respect shown to the surrounding neighbourhood and its residents.

Angular planes are arguably effective at accomplishing their stated purpose—they do a good job of preserving sunlight. However, by reducing floor space within the upper levels of a building, they also constrain the number of new housing units it can have. This is why, as Toronto’s housing crisis continues to worsen, the angular plane requirement has become increasingly controversial.

While high-rise condominiums are a signature feature of the downtown core, they are also clustered at certain transit and highway nodes throughout Toronto. Restrictions limit development in many residential areas of the city—particularly in areas bordering the city’s large inventory of single-family neighbourhoods, known as the Yellowbelt. The development that is permitted in these areas is generally mid-rise and limited to the main streets of these communities. Both high rises and mid-rises are subject to angular plane requirements, but those rules have a far greater impact on mid-rise projects. Since high rises, by their nature, contain a large number of units, the reductions forced by the angular planes represent a much smaller percentage of the total. In mid-rises, which start out with comparatively fewer units, losing even a small number of them to the angular plane constraint can increase the overall cost of construction substantially.

Recently, many planners having been calling attention to the negative impacts of this provision, noting that the focus on minimizing shadow impacts can be a major roadblock to other vital planning objectives, such as environmental sustainability, the creation of new housing, and especially housing affordability. (Following common practice in the sector, the City defines affordability as “housing where the total monthly shelter cost is at or below the lesser of one times the average City of Toronto rent, by dwelling type, or 30% of the before-tax monthly income of renter households.”)

Toronto’s mid-rise angular plane provision drives up the cost of a housing development in a few ways. The step backs on each floor create additional construction costs as the building’s architecture and floor plans increase in complexity. As well, there are real revenue implications associated with the loss of units on upper floors: a smaller profit margin means that housing providers need to charge more per unit. In some cases, angular planes can have such a detrimental impact on the feasibility of a development that it never gets built at all.

While high-rise condominiums are a signature feature of the downtown core, they are also clustered at certain transit and highway nodes throughout Toronto. Restrictions limit development in many residential areas of the city—particularly in areas bordering the city’s large inventory of single-family neighbourhoods, known as the Yellowbelt. The development that is permitted in these areas is generally mid-rise and limited to the main streets of these communities. Both high rises and mid-rises are subject to angular plane requirements, but those rules have a far greater impact on mid-rise projects. Since high rises, by their nature, contain a large number of units, the reductions forced by the angular planes represent a much smaller percentage of the total. In mid-rises, which start out with comparatively fewer units, losing even a small number of them to the angular plane constraint can increase the overall cost of construction substantially.

Recently, many planners having been calling attention to the negative impacts of this provision, noting that the focus on minimizing shadow impacts can be a major roadblock to other vital planning objectives, such as environmental sustainability, the creation of new housing, and especially housing affordability. (Following common practice in the sector, the City defines affordability as “housing where the total monthly shelter cost is at or below the lesser of one times the average City of Toronto rent, by dwelling type, or 30% of the before-tax monthly income of renter households.”)

Toronto’s mid-rise angular plane provision drives up the cost of a housing development in a few ways. The step backs on each floor create additional construction costs as the building’s architecture and floor plans increase in complexity. As well, there are real revenue implications associated with the loss of units on upper floors: a smaller profit margin means that housing providers need to charge more per unit. In some cases, angular planes can have such a detrimental impact on the feasibility of a development that it never gets built at all.

Case Study: Our Site and Project

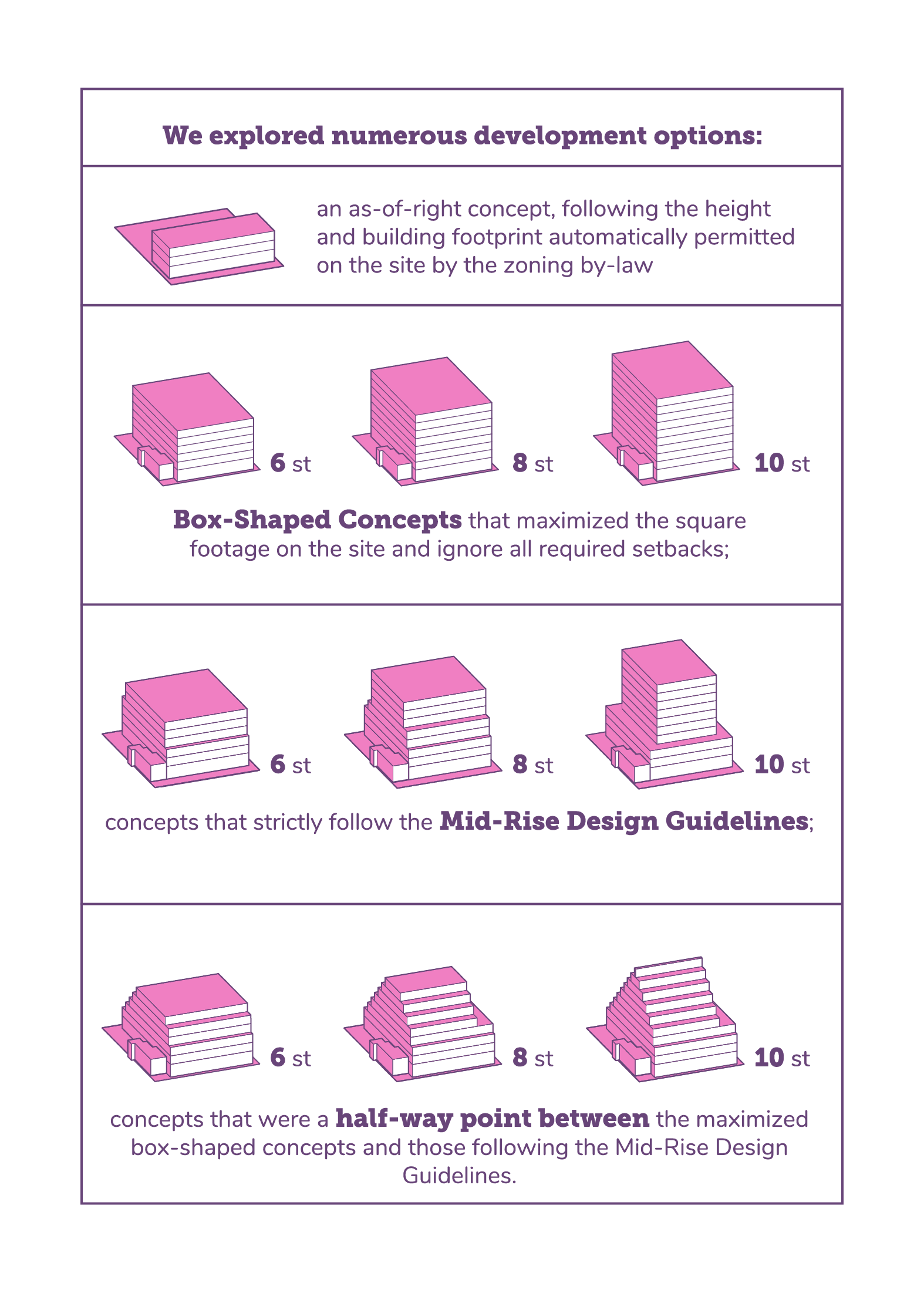

In the fall of 2021, our team of 12 students from the Advanced Planning Studio II course at Toronto Metropolitan (formerly Ryerson) University was retained to work with HousingNowTO, a not-for-profit collective seeking to ensure that the City maximizes the provision of affordable housing on its properties. Our task was to propose an affordable housing development concept for a surplus city-owned site, at 1113–1117 Dundas Street West. With the guidance of HousingNowTO and our studio adviser, we worked to determine the optimal development option for the site, with the goal of maximizing the number of affordable housing units that could be built.

In the course of this process, we quickly realized that, while higher-level policies (such as the Provincial Policy Statement, the A Place to Grow plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, and Toronto’s Official Plan) all support the creation of new housing that is affordable for a range of incomes, lower-level policies and guidelines (such as the zoning bylaw and mid-rise design guidelines, which include the angular plane requirement) make this form of housing extremely difficult to build.

When it came to the first option—what was permitted as of right—the site’s restrictive zoning precluded the creation of additional new density. The setback requirements and limits on permitted height, depth, and floor space index made any conforming building too small to feasibly support affordable housing.

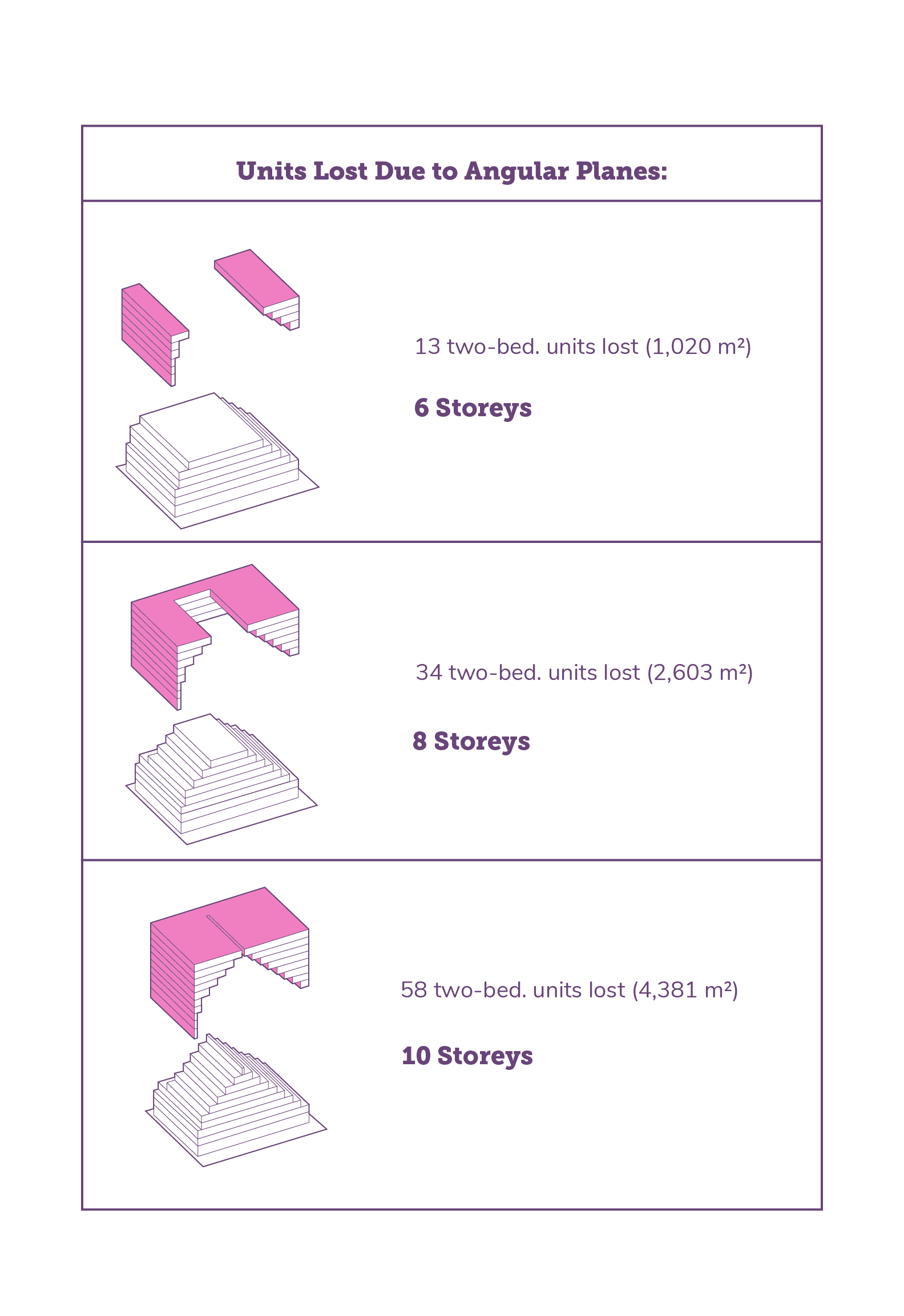

Similarly, and perhaps even more significantly, the mid-rise design guidelines dictated an angular plane requirement that forced the removal of up to 4,381 square metres of floor space for housing in our development concepts. In our tallest design option (10 storeys), this was equivalent to losing 58 two-bedroom units, amounting to a loss of $1,086,084 in potential gross revenue. All concepts that followed the mid-rise design guidelines lost a significant number of units, which became more apparent as height increased.

In the fall of 2021, our team of 12 students from the Advanced Planning Studio II course at Toronto Metropolitan (formerly Ryerson) University was retained to work with HousingNowTO, a not-for-profit collective seeking to ensure that the City maximizes the provision of affordable housing on its properties. Our task was to propose an affordable housing development concept for a surplus city-owned site, at 1113–1117 Dundas Street West. With the guidance of HousingNowTO and our studio adviser, we worked to determine the optimal development option for the site, with the goal of maximizing the number of affordable housing units that could be built.

In the course of this process, we quickly realized that, while higher-level policies (such as the Provincial Policy Statement, the A Place to Grow plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, and Toronto’s Official Plan) all support the creation of new housing that is affordable for a range of incomes, lower-level policies and guidelines (such as the zoning bylaw and mid-rise design guidelines, which include the angular plane requirement) make this form of housing extremely difficult to build.

When it came to the first option—what was permitted as of right—the site’s restrictive zoning precluded the creation of additional new density. The setback requirements and limits on permitted height, depth, and floor space index made any conforming building too small to feasibly support affordable housing.

Similarly, and perhaps even more significantly, the mid-rise design guidelines dictated an angular plane requirement that forced the removal of up to 4,381 square metres of floor space for housing in our development concepts. In our tallest design option (10 storeys), this was equivalent to losing 58 two-bedroom units, amounting to a loss of $1,086,084 in potential gross revenue. All concepts that followed the mid-rise design guidelines lost a significant number of units, which became more apparent as height increased.

Our key finding, in short, was that contradictory higher-and lower-level policies serve as a strong deterrent to the development of new housing in Toronto and especially housing that meets the city’s definition of affordability. In fact, municipal rules directly impede it.

Our key finding, in short, was that contradictory higher-and lower-level policies serve as a strong deterrent to the development of new housing in Toronto and especially housing that meets the city’s definition of affordability. In fact, municipal rules directly impede it.

ANGULAR PLANES, Toronto tells us, represent an attempt to respect our neighbours. But the creation of affordable housing is also a form of respect: respect for newcomers wanting to move to Toronto, respect for lower-income individuals who deserve to be able to live close to where they work, and respect for young adults trying to invest in their first home. In the context of Toronto’s current housing crisis, we need to consider our priorities as a city. Should we continue to prioritize sunlight in the backyards of the few who can afford single-detached housing in the city—or should we focus on building as much new housing supply as possible? There are many vibrant, livable cities around the world that have grown more organically without the angular plane requirement. Think of Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona: cities that many of us like to travel to for their charm, walkable streets, and diverse architecture. These places have proven that walkability, livability, and resilience are all possible—and perhaps even more likely—without the angular plane.

Julia Covelli, Tatiana Guzman, Connor Joy, and Chantel Watkins are urban and regional planning students at Toronto Metropolitan University. This article is based on a group studio project they completed for HousingNowTO in 2021 with their peers Tony Chow, Athaven Joshua Jeyamohan, Jake Lisser, Anthony Mancini, Addison Milne-Price, Shayan Okhowat, Thomas Tingchaleun, and Yvonne Ye.