Time to Get Serious About Non-Market Housing

Non-market housing is in crisis—and that's a problem for residents in every other kind of home, too. It's time to rebalance our housing ecosystem.

- Helen Lui

- Mar 1, 2023

Photo by Brandon Griggs via Unsplash

I HAVE BEEN WORKING for a non-profit, non-market housing developer and operator for six years and in the development industry for nearly a decade; my work focuses on providing rental housing for people with low to moderate incomes. I’ve completed projects ranging from small townhomes to larger mixed-use buildings with non-market rental units, and I’ve worked with a variety of municipalities, ranging from large urban centres such as Vancouver to growing cities like Port Moody and small communities such as Tofino. And now, like never before, I am seeing a strong surge of political and community support in Canada for new affordable housing, with non-market housing featuring as a highlight in the discussion.

But what is non-market housing and why is it important?

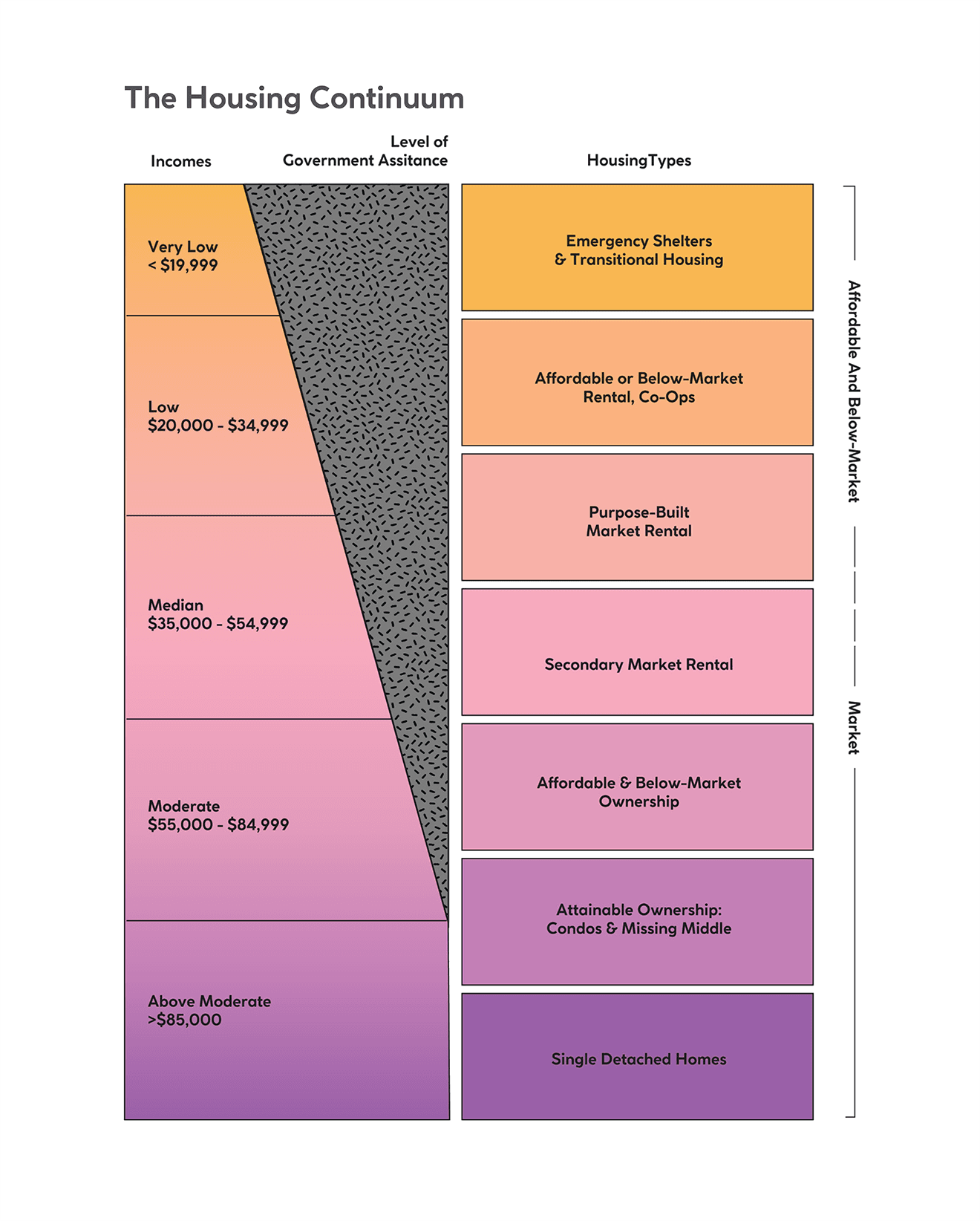

Simply put, non-market housing is intended for households that have difficulty accessing or affording market-rate homes. Typically, non-market homes have protections that come through the regulations and operating agreements that define non-market housing projects; these can include caps on annual rent increases, correlating permissible rents to median or average incomes, and requiring that rent be geared to household incomes. Non-market housing is most often created to provide homes to people with low to moderate incomes, but other goals include creating alternate ownership models (such as co-ops), providing assisted and supportive housing, and creating housing that can be reserved for vulnerable populations, such as individuals fleeing from violence. It is an important and crucial part of the housing mix in any community.

Non-market housing can be owned and/or operated by government, non-profits, or for-profit organizations, but is often made feasible with government assistance or subsidies—which, in turn, require agreements with owners and operators to ensure the affordability and security of the housing that’s being funded. Those who work in the non-market housing space usually define housing as “affordable” when a household spends no more than 30% of its income on housing costs. Applicants are typically income tested in order to qualify for this housing to ensure that they are within the targeted income range.

Though the current level of attention is novel, non-profit housing is not a new concept: it has existed in Canada for decades. Today in BC, there are over 800 non-profit housing providers operating approximately 70,000 homes. In Ontario, there are currently more than 700 non-profit housing providers; they provide over 170,000 homes.

The new focus on non-market housing does signal something important about the current state of housing in Canada, however. Where there isn’t enough housing of any type in a community, the cost of the scarce housing that is available goes up. This forces people with lower incomes into unsafe and insecure housing, as they have the least leverage and ability to compete for the limited housing options. In such a context, only those with the highest incomes can safely and adequately meet their housing needs.

The really crucial thing to realize about non-market housing is that it is one element in a whole housing ecosystem: the term “housing continuum” is often used to describe the spectrum of housing options that can be available, arrayed according to income and the level of government subsidy or support involved.

In order to understand how non-market housing can expand and what problems it can (and cannot) solve, we need to talk about the regulatory framework that governs all new housing development and we need to talk about the state of market (for-profit) housing. Building codes, zoning approvals, and other factors that limit or slow the development of for-profit housing affect non-market housing as well. Thriving cities require robust market and non-market housing: they complement each other, and insufficient housing in one segment puts pressure on the other.

There’s a concept in planning theory called the filtering effect. Essentially, filtering is the idea that even when you build housing that isn’t affordable to some, it has a positive impact on the overall housing situation because it means those who can afford the higher cost of housing will free up more moderately priced homes. We need abundant housing options at all price points to ensure folks can move easily between housing typologies and costs.

In the context of our current housing-affordability crisis, non-market housing is in crisis too. Land-use regulations in Canada tend to be quite restrictive; this affects how much new housing of any type can get built, including non-market housing. Recent changes in the industry mean that even projects that have free land and provincial or federal government financing are still infeasible. And non-market projects will only become more challenging as construction costs and interest rates go up. Making non-market projects work will require a multitude of measures to address both the challenging overall regulatory framework and the unique complexity of non-market projects.

In order to understand how non-market housing can expand and what problems it can (and cannot) solve, we need to talk about the regulatory framework that governs all new housing development and we need to talk about the state of market (for-profit) housing. Building codes, zoning approvals, and other factors that limit or slow the development of for-profit housing affect non-market housing as well. Thriving cities require robust market and non-market housing: they complement each other, and insufficient housing in one segment puts pressure on the other.

There’s a concept in planning theory called the filtering effect. Essentially, filtering is the idea that even when you build housing that isn’t affordable to some, it has a positive impact on the overall housing situation because it means those who can afford the higher cost of housing will free up more moderately priced homes. We need abundant housing options at all price points to ensure folks can move easily between housing typologies and costs.

In the context of our current housing-affordability crisis, non-market housing is in crisis too. Land-use regulations in Canada tend to be quite restrictive; this affects how much new housing of any type can get built, including non-market housing. Recent changes in the industry mean that even projects that have free land and provincial or federal government financing are still infeasible. And non-market projects will only become more challenging as construction costs and interest rates go up. Making non-market projects work will require a multitude of measures to address both the challenging overall regulatory framework and the unique complexity of non-market projects.

Who’s Involved?

At the core of most non-market housing projects is a strong partnership, often between non-profits, developers, and/or governments working with a housing operator. In many cases, one of these partners already owns land that is available for housing. These partnerships allow groups to bring together equity and expertise, but they also add complexity; each of these relationships need to be clearly defined to minimize risk. Legal agreements outline the ownership, delivery, operating models, and outcomes of these projects. Each partner also needs to answer to numerous committees, boards, and oversight bodies—which sometimes have competing values and priorities. It can take up to five years for a partnership to be established and documented before the design process can even get underway. As with all complex developments, in non-market housing, the various partner’s interests overlap but can also conflict. In one case, a project of ours was on standstill for months because different government organizations couldn’t agree about which of them should appear first on the title (and get first right to expropriate the property if the mortgage went unpaid). Such periods of risk and delay increase a project’s costs, resulting in higher rents—precisely what these developments are meant to avoid.

How Is Non-Market Housing Delivered?

One might assume that—because non-market housing is designed to support vulnerable people and meet a social need—municipal governments would expedite approvals for those projects. While many governments prioritize these applications, in all of the municipalities where I have worked, non-market housing developments face the same zoning and land-use regulations as market housing does, which often slows things down considerably. Any housing project that calls for adding height or density requires discretionary approvals; obtaining these is a lengthy process and can involve contentious public hearings. All this is true even when projects conform with neighbourhood plans, help meet city housing-affordability goals, and satisfy municipal or provincial building performance targets.

On projects I’ve been involved with, it has taken anywhere from 12 to 36 months to get rezoning and development permit approvals. On one project, we made seven different submissions for our rezoning and development permits, as a result of 10 rounds of (sometimes conflicting) comments from various municipal departments. It took 34 months for our rezoning and development permit approvals to come through, even when the land and financing were in place.

The risk here is not only in the time it takes to move a project forward but also in the lack of certainty and clarity about the requirements a development must satisfy. Sometimes, land-use regulations, city goals, and external government entities have conflicting requirements, resulting in lengthy negotiations that add to a project’s costs and ultimately make it less affordable for tenants. (The few times I haven’t encountered this have been in very small communities where clear and straightforward regulations are coupled with municipal urgency around housing needs.) At the same time, other elements of the project may also still be in flux, adding further risk: interest rate changes, depletion of provincial and federal funding or grants, and construction cost increases all take a toll.

Many municipalities are working to create or change their policies and make non-market housing approvals more efficient, but they are encountering challenges along the way.

In Vancouver, city council recently enacted a policy that permitted the development of secured rental buildings up to six storeys in key corridors across the city, without requiring a rezoning for each individual project. This was an amendment to an existing policy that staff had begun to work on in the summer of 2018. At that time, I was involved with two non-profit, non-market projects in Vancouver that would qualify under the amended policy. We worked with staff in hopes that the project applications could be submitted once the amended policy was approved, as it would save us substantial time and expense and allow for lower rents.

Council wound up sending the policy back to staff for further community consultation; the amendment was not approved until December 2021. The delay, uncertainty, and carrying costs undermined both of the projects I was involved with. One of the sites was sold to a for-profit developer, who will be building less-affordable market-rate rental units. At the second site, the delays were too lengthy, and we opted to pursue a rezoning, which incurred additional costs that were reflected in higher rents. Ultimately, additional risk and delay causes increased costs, which are almost always passed on to the final tenants.

The risk here is not only in the time it takes to move a project forward but also in the lack of certainty and clarity about the requirements a development must satisfy. Sometimes, land-use regulations, city goals, and external government entities have conflicting requirements, resulting in lengthy negotiations that add to a project’s costs and ultimately make it less affordable for tenants. (The few times I haven’t encountered this have been in very small communities where clear and straightforward regulations are coupled with municipal urgency around housing needs.) At the same time, other elements of the project may also still be in flux, adding further risk: interest rate changes, depletion of provincial and federal funding or grants, and construction cost increases all take a toll.

Many municipalities are working to create or change their policies and make non-market housing approvals more efficient, but they are encountering challenges along the way.

In Vancouver, city council recently enacted a policy that permitted the development of secured rental buildings up to six storeys in key corridors across the city, without requiring a rezoning for each individual project. This was an amendment to an existing policy that staff had begun to work on in the summer of 2018. At that time, I was involved with two non-profit, non-market projects in Vancouver that would qualify under the amended policy. We worked with staff in hopes that the project applications could be submitted once the amended policy was approved, as it would save us substantial time and expense and allow for lower rents.

Council wound up sending the policy back to staff for further community consultation; the amendment was not approved until December 2021. The delay, uncertainty, and carrying costs undermined both of the projects I was involved with. One of the sites was sold to a for-profit developer, who will be building less-affordable market-rate rental units. At the second site, the delays were too lengthy, and we opted to pursue a rezoning, which incurred additional costs that were reflected in higher rents. Ultimately, additional risk and delay causes increased costs, which are almost always passed on to the final tenants.

How Is It Viewed?

Non-profit projects often face heavy scrutiny because they are funded with the help of public investment from various levels of government. Despite efforts to be open and transparent about a project’s challenges, politicians and the general public alike can be skeptical of the information shared with them. At the extreme, this dynamic will see politicians vote against their own stated goals. In one instance I know of, city councillors defeated a project that was on a municipal property, which they themselves designated specifically for affordable housing, due to public opposition to the proposed height and density. (Lower heights or densities would not have been feasible at this site.) The municipality had a mandate to add affordable housing, it had set aside land for the purpose, and council had directed staff to expedite the project. After the non-profit developer spent a year and nearly half a million dollars on the development application, council shut it down. Such incidents only heighten the (perceived) risks of such endeavours and further weaken the already very limited non-market sector capacity. The burgeoning interest in non-market housing notwithstanding, the public is not always receptive when it comes to specific development proposals. In community consultations, many people often complain that the housing is too affordable (this is often accompanied by discriminatory assumptions about the anticipated tenants) while others lament that rents are not affordable enough.

Who Pays?

Most non-profit, non-market housing projects are strapped for cash; they aren’t necessarily getting enough public funding to cover a development’s full costs, and the onus is still on the partners to make the project viable. The land is usually the biggest—and only—financial asset the project has. The majority of non-market housing is made feasible through subsidies at the time of construction and sometimes on an ongoing basis. These primarily come from various levels of government, but projects can also be supported by private social-purpose investors. At the federal level, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) provides a variety of grants and low-cost financing when delivering non-market housing. Various provinces and territories have their own mechanisms to support such projects. BC Housing is a Crown agency that develops and operates its own non-market housing, to take one example; it also provides grants and financing to other non-market developers and operators. In Toronto, the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) owns and operates housing with support from the city. Many municipal and regional governments also support non-market housing by waiving portions of development costs or sometimes by providing grants that are funded via fees levied on market housing developments. In nearly all of my work, the grants and financing that governments provide are based on strict rules, coupled with rigorous stress testing and application requirements. These can include metrics such as affordability targets, rent rate guidelines, and design criteria such as unit sizes, unit mix, or energy performance. Each condition typically comes with one-time or ongoing reporting requirements, and each financing partner has its own rules and reporting standards. Non-market projects often require multiple funding sources and supports. This means that developers need to submit multiple applications, each with their own requirements—requirements that are often misaligned and use completely different metrics. For example, CMHC’s programs measure affordability using their own median rent rates, or income data often based on averages of the overall proposed rents. Meanwhile, BC Housing’s programs have their own affordability metrics and often require a fixed percentage of units be built at different levels of affordability. Grants and financing programs also often use different methods of underwriting, including different amortization periods and different stress test rates, which further exacerbate the problem: a proposed set of rents may qualify for one program but not another. Finally, the biggest challenge might be the heavy-handed, top-down operating agreements that non-market housing providers must sign in order to receive funds. These often come with overwhelming terms; for example, if loan mortgage payments aren’t made, lenders may expropriate the property and do with it what they wish—including sell to the highest bidder. Other terms may limit what rental income may be used for—including restrictions on using surpluses to develop future non-market housing. For non-profit and non-market housing operators, such constraints add huge risk to their already tight financials, and further weaken their ability to take on new projects.

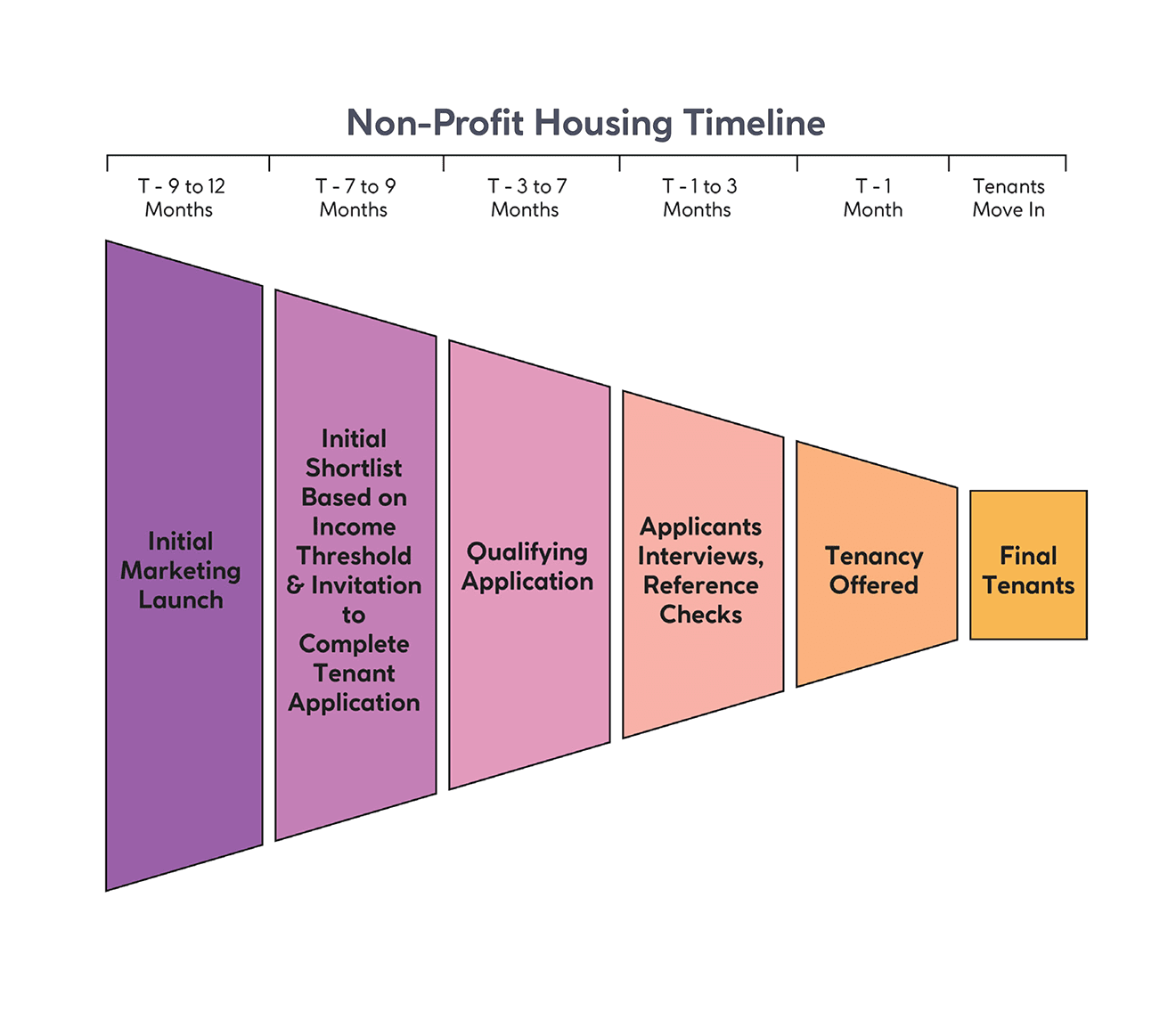

Affordable Housing for All

The challenges that I’ve just described all add risk, delay, and cost to non-market housing projects. Meanwhile, even non-market housing incurs constructions costs at market rates, which are sharply increasing every year. There are no non-profit contractors or consultants (that I know of). The result? Slow and ineffective delivery of much-needed housing that could be much more affordable than it winds up being. Where non-market or non-profit partners are ready to address and add non-market housing, it is often regulatory processes and challenging government bureaucracy that limit their capacity and delivery. On a recent small project I completed in the Lower Mainland in BC, we received over 100 applications for the three non-market townhomes in the development. This is not atypical; in Vancouver, Toronto, and many other urban regions, there are long waitlists for non-market housing, as well as tenants who are willing to spend more than 30% of their income on the new non-market homes because it is an improvement over their current housing situation. Typically, there are many more qualified applicants than available affordable housing. Most tenant selections are ultimately made via lottery—it’s one way to eliminate bias in the selection process. Non-Market Tenancy Funnel and Timeline All levels of government need to improve. The quickest way to ensure that there is sufficient non-market housing is by creating a quick and efficient process for delivery of non-market units as well as sufficient government subsidies to support them. Here are some places to start: *Clarify and add predictability to the approvals process. *Where projects meet community plans and city goals, streamline approvals by implementing city-wide, by-right zoning. *Clearly prioritize the goals for affordable housing in any given community so that non-market developers know what the greatest needs are. *Align metrics and requirements across all levels of government—specifically around targeted rent rates, sustainability, and other outcomes. *Improve communication and public education about the housing continuum and the various types of non-market housing. *Increase government grants and financing options for non-profit and non-market housing across all levels of government. *Reduce the barriers and requirements to government grants and financing and align metrics and requirements across levels of government. (Un)surprisingly, most of the above applies not only to non-profit, non-market housing but also to for-profit developments. Non-profit housing developers are still developers: the challenges we face to delivering good, affordable housing are not unique to non-profit work but a function of inefficient processes that slow down and limit all kinds of developments. Non-market or non-profit housing on their own cannot meet the full continuum of housing needs; they are not a cure-all for our housing crisis. In order to achieve affordable housing for all, we need to ensure an abundance of options both in non-market and market housing. Affordable housing shouldn’t be a specific type of housing; instead, it should define a condition where all people, at all income levels, can afford the housing they need. We will attain this when all housing providers, non-market and market alike, have to compete for tenants and buyers—who will have abundant options on the housing continuum and be able to choose the ones that genuinely meet their needs and fit their budgets.

Helen Lui is a development manager who has led a variety of mixed use and residential projects and has extensive experience in non-profit housing partnerships and developments.